In November 2024, Egypt achieved a historic milestone: certification as malaria-free by the World Health Organization (WHO). This designation, granted to only 44 countries and one territory globally, highlights Egypt’s nearly century-long battle against a disease that once posed a significant threat to its public health and economic productivity.

Malaria remains one of the world’s deadliest diseases, infecting over 200 million people annually and causing more than 600,000 deaths. According to WHO, 95% of malaria cases and deaths occur in Africa, with children under five and pregnant women most affected. The disease thrives in tropical climates, where poverty, limited healthcare access, and inadequate infrastructure exacerbate its impact.

By 2024, Egypt became one of only five African nations—joining Mauritius, Morocco, Algeria, and Cabo Verde—to achieve malaria-free certification. This status means that indigenous malaria transmission has been interrupted for at least three consecutive years and that Egypt has demonstrated the capacity to prevent its re-establishment.

Egypt’s journey against Malaria

Since the early 20th century, Egypt has worked tirelessly to combat malaria, turning a once-endemic disease into a historical footnote. Key milestones on this journey include:

1920s-1930s: Early control efforts

In the 1920s, malaria cast a long shadow over Egypt, particularly in rural areas. The government’s efforts to drain swamps and clear mosquito breeding sites marked the beginning of a fight that would last nearly a century.

1940s-1950s: Introduction of DDT (Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) and regional collaboration

During World War II, malaria cases surged to nearly 30,000 annually due to widespread disruption. In response, Egypt adopted DDT for indoor residual spraying, a significant advancement in vector control. In 1955, the country joined the WHO Global Malaria Eradication Program, strengthening its collaboration with neighboring countries, including Sudan, to coordinate cross-border efforts and share epidemiological data.

1960s-1980s: Significant reduction in cases

Systematic spraying, enhanced surveillance, and effective treatments reduced cases significantly. By the 1970s, annual cases dropped to fewer than 1,000, supported by cross-border partnerships with Sudan and Libya.

1990s-2000s: Strengthened surveillance and international initiatives

In the 1990s, Egypt implemented advanced epidemiological surveillance systems to quickly detect malaria cases, especially in border regions. It also collaborated with the Roll Back Malaria (RBM) Partnership, aligning its strategies with neighboring countries to prevent a resurgence of the disease.

2014: Rapid response to local cases

When indigenous malaria cases appeared in the Aswan region in 2014, Egypt acted swiftly. Authorities intensified surveillance, conducted targeted spraying, and distributed insecticide-treated mosquito nets. Close coordination with Sudan ensured the outbreak was contained.

Since 2016: Sustained efforts and regional collaboration

Since 2016, Egypt has maintained rigorous surveillance, trained healthcare workers, and run public awareness campaigns in high-risk areas. Cross-border collaboration and data sharing have been vital in preventing the disease’s return. These efforts culminated in WHO certifying Egypt as malaria-free in 2024.

Source:

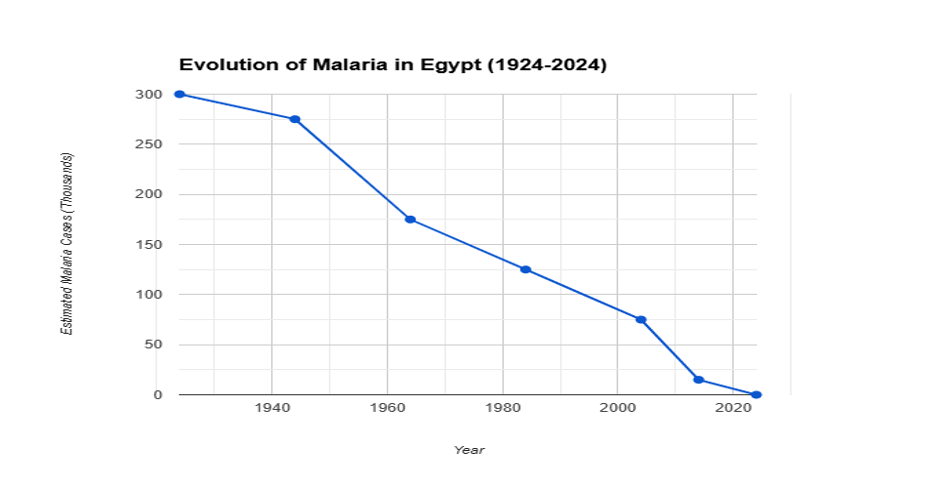

Evolution of Malaria in Egypt

Note: Data in this graph is estimated and intended for illustrative purposes, based on historical malaria trends and WHO-reported progress in Egypt.

Egypt’s model: integrated and collaborative

Egypt’s success in fighting malaria shows how powerful an integrated approach can be. The country combined several strategies to tackle the disease, including spraying insecticides, draining wetlands to reduce mosquito breeding areas, distributing mosquito nets, and providing anti-malaria treatments. These efforts were supported by stronger healthcare services, giving more people access to testing and treatment.

The Egyptian government’s leadership played a critical role in this progress. Significant investments in public health, including funding for malaria control programs, showcased its dedication to eradicating the disease. Policies were designed to address the needs of vulnerable communities, particularly those in rural and high-risk areas. Government-led awareness campaigns educated communities on malaria prevention and the importance of early treatment, empowering people to take action against the disease.

Partnerships with international organizations, like the WHO and RBM Partnership, were very important for Egypt’s success. These collaborations gave Egypt access to expert advice, shared knowledge, and effective strategies. Egypt also worked closely with neighboring countries, such as Sudan, to coordinate efforts across borders. Together, they shared data, planned actions, and stopped malaria from spreading between their countries

Together, these integrated efforts helped Egypt earn WHO’s malaria-free certification in 2024, showing that even in challenging environments, eliminating malaria is possible with a focused and united effort.

Socioeconomic impact: beyond health

Malaria’s effects extend far beyond health. Its elimination has brought profound socioeconomic benefits to Egypt:

- Lower healthcare costs: Families and the government save significantly on malaria-related treatments.

- Improved education: Children miss fewer school days due to illness, enhancing educational outcomes.

- Boosted agricultural productivity: A healthier workforce has led to higher crop yields

These results highlight why malaria control is not just a public health measure but an investment in long-term economic development.

A blueprint for Africa

In 2023, Africa faced the largest burden of malaria, with 94% of all cases worldwide—246 million people, each one part of a family struggling with this preventable disease—and 95% of malaria-related deaths, totaling 569,000. (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malaria)

Heartbreakingly, about 80% of those deaths were children under five. Four countries—Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda, and Mozambique—accounted for more than half of these losses. These numbers make it clear: tackling malaria is not just important—it is urgent.

Egypt’s success offers hope. It proves that malaria can be defeated with strong government leadership, active community involvement, and strategic planning. By prioritizing healthcare, raising awareness, and fostering partnerships, African countries can adapt Egypt’s approach and develop solutions tailored to their unique challenges.

Emerging technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) also present exciting opportunities. AI offers several opportunities in malaria management, including early detection and prediction of outbreaks, improved diagnosis, personalized interventions, optimal treatment recommendations, surveillance and response, resource optimization, and research innovation. (Ogbaga, 2023)

Local organizations, NGOs, and community leaders also play pivotal roles. By educating families, promoting the use of mosquito nets, and supporting prevention programs, they help build resilient communities that can effectively combat malaria.

Finally, we must remember the most vulnerable—children and families in underserved and remote areas. Their lives matter deeply. Every child saved from malaria is a step closer to a brighter future. Inspired by Egypt’s journey, we can dare to imagine—and work toward—a malaria-free Africa, where no life is lost to this preventable disease.

References:

World Health Organization. (2024). Egypt is certified malaria-free by WHO. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/news/item/20-10-2024-egypt-is-certified-malaria-free-by-who

World Health Organization. (2024). Malaria fact sheet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malaria