Benissan Barrigah – edited by PACT

Financing, Institutions, and Human Development in 2025

2025 was characterized by notable shifts in Africa’s financial landscape. The abrupt withdrawal of certain bilateral financing, particularly from USAID, revealed the continued dependence of many social systems on concessional assistance. The contractions observed in the health and education sectors underscored that the transition toward more autonomous domestic financing mechanisms remains incomplete.

Rising gold prices and the growing strategic importance of critical minerals have given Africa’s extractive industries increased macroeconomic and geopolitical weight, placing them at the center of energy-transition value chains and global supply-security strategies. In Mali and Guinea, the commissioning of lithium projects and progress on the Simandou project illustrate this trend. In several countries, these prospective revenues have revived interest in sovereign wealth funds as instruments for stabilization and investment. The challenge now lies in aligning these funds with budgetary frameworks and with productive projects capable of transforming extractive rents into durable assets.

Access to international capital markets partially reopened in 2025, but only selectively and at high cost. After a sharp contraction in international sovereign bond issuance in 2023, a few countries, including Côte d’Ivoire, Angola and Nigeria, were able to take advantage of a market window. However, most issuances were directed primarily toward refinancing existing debt rather than financing new productive capacity. In this context, the African Development Bank, under the leadership of President Dr. Sidi Ould Tah, sent a strong institutional signal by combining a strategic reorientation with a record replenishment of the African Development Fund to around USD 11 billion, along with a reinforced focus on developing African capital markets.

The mobilization of domestic capital is advancing, but remains incomplete. Regional debt markets continue to be dominated by sovereign borrowing and bank balance sheets, while pension funds remain underexposed to SMEs and non-sovereign infrastructure because of a shortage of appropriate instruments and restrictive prudential frameworks.

At the same time, West African fintech has entered a phase of regulatory normalization under the impetus of the BCEAO. Actors such as Wave and Moniepoint demonstrate that fintech neither replaces banks nor capital markets; rather, it constitutes one of the main entry points for the informal sector into the financial system, by making financial flows traceable and generating transaction histories that could, over time, facilitate access to credit.

These dynamics converge toward a central question: the relationship between financial architecture and human development. The social and security tensions observed in several countries highlight how insufficient sustainable investment in education, health, and energy weighs on growth, fiscal stability, and security. Capital has economic relevance only insofar as it translates into the accumulation of human capital, the absorption of rapid demographic growth, and the creation of productive employment.

The test in the years ahead will concern not only the ability to mobilize resources, but also the extent to which they are transformed into gains in productivity and human development. The credibility of African trajectories will hinge on this concrete alignment between capital markets, public policy, and economic inclusion.

I. USAID and the reconfiguration of the aid ecosystem

In 2025, the refocusing of several USAID instruments under the Trump administration contributed to a reconfiguration of external financing in many African countries. The Rescissions Act of 2025 cancelled several billion dollars in international assistance and led to the suspension or scaling-down of multiple programs, generating funding disruptions in health, education, and humanitarian activities and contributing to a contraction of local capacities.

In the health sector, reliance on U.S. financing was a major transmission channel. Adjustments to programs linked to PEPFAR resulted in reductions in planned activities and financing envelopes in several countries, with differentiated impacts depending on country exposure. These reductions affected pharmaceutical supply chains, service-provider contracts, and prevention activities. The President’s Malaria Initiative also faced significant budgetary pressure, with consequences for national prevention and treatment capacity.

The decline in U.S. contributions to multilateral mechanisms, including UN agencies, was accompanied by a marked fall in available humanitarian resources between 2024 and 2025. This shifted priorities across crises and led to program resizing in a number of African contexts. Local and international NGOs, often integrated into financing chains partly backed by U.S. resources, also experienced liquidity constraints and challenges to operational continuity.

These adjustments highlighted how deeply U.S. concessional assistance is embedded in sectoral and budgetary equilibria. In many low-income and lower-middle-income countries, a significant share of non-wage social spending depends on external grants. The rapid contraction of these flows generated short-term trade-offs, including the postponement of recurrent investments, a refocusing on emergency responses, and the discontinuation of some non-priority interventions. Exposure varied from country to country depending on the relative weight of U.S. assistance in social sectors.

The effects observed therefore extended beyond the perimeter of USAID itself, bringing three key questions back to the forefront: the actual share of domestic revenues financing social services, the degree of dependence on a dominant donor, and the feasibility of rapidly diversifying funding sources. In the background lies a central issue: the capacity of States to finance essential social policies from domestic resources, independently of aid cycles.

II. Natural resources: productive sectors and macroeconomic levers

In 2025, natural resources assumed a greater role in macroeconomic decision-making, driven by the combined effects of high gold prices and continued tensions surrounding critical minerals. This context strengthened their role as generators of foreign exchange and as instruments of fiscal and external adjustment.

In Mali, the start of export-oriented lithium production, and in Guinea, progress on the Simandou project, structured around major mining and large-scale infrastructure investments, have illustrated the growing integration of natural resources into states’ macroeconomic choices. These projects are now embedded in budget decisions, debt strategies, and infrastructure planning, rather than being treated solely as export sectors. In Côte d’Ivoire, the Ambition 2035 strategy, underpinned by oil prospects, follows the same logic by using hydrocarbons as a lever for financing infrastructure and economic transformation, while simultaneously exposing the country to the risks associated with market volatility.

The core issue has not been the increase in extraction volumes, but rather the macroeconomic transmission of revenues: the design of fiscal regimes, the modalities of State and operator revenue sharing, local-content requirements, choices on budgetary allocation, and linkages with infrastructure projects. These parameters determine the effective impact on public debt, external sustainability, and productivity.

The growing operation of the Dangote refinery in Nigeria represents a measurable turning point in regional energy markets, as the substitution of imported petroleum products with locally refined fuel has reduced Nigeria’s reliance on fuel imports and altered external trade flows, while anchoring capital-intensive industrial capacity. It highlights the macroeconomic gap between crude exports and domestic transformation.

This perspective calls for moving beyond the “resource curse” paradigm. Trajectories associated with natural resources depend less on the nature of deposits than on choices regarding transformation, industrial integration, and the use of revenues, which shape both diversification of the productive base and the capacity to absorb price shocks.

III. Sovereign wealth funds: sovereignty ambitions and governance challenges

In 2025, sovereign wealth funds strengthened their role as instruments for managing public revenue volatility in Africa, in a context of fiscal constraints and elevated debt levels. Angola, Guinea, Botswana, and Côte d’Ivoire illustrate this trend, with arrangements at various stages of announcement, creation, restructuring, or operationalization.

Sovereign wealth funds are generally expected to perform three main functions: cushioning shocks associated with extractive revenues, building long-term savings, and financing infrastructure. Their effectiveness depends on how they are designed and governed, including the source of their resources, the rules for withdrawals, the separation of stabilization and investment mandates, and their alignment with fiscal and debt policy. Where these frameworks are weak, funds risk becoming parallel channels for public spending rather than instruments of macroeconomic stabilization.

In Angola, the repositioning of the Fundo Soberano de Angola reflects an effort to deploy capital more actively. In 2025, the fund announced, together with Gemcorp Capital, a pan-African infrastructure vehicle of up to USD 500 million. This turn toward co-investment signals a shift from a passive portfolio-management approach to one oriented toward bankable projects in energy, water, natural resources, and the energy transition. The decisive issue now is the translation of these announcements into actual disbursements and the development of a credible project pipeline.

More broadly, the developmental impact of sovereign wealth funds stems from their ability to influence the structure of investment. As anchor investors, they can absorb part of the initial risk, extend investment horizons, and attract institutional capital. International experience, including the Pula Fund in Botswana and the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund, shows that such outcomes are most likely when rules for deposits and withdrawals are clearly defined, financial management is insulated from day-to-day political intervention, and resource revenues are managed with a long-term perspective.

Ultimately, the key question is not whether new funds are created, but how existing and emerging funds are integrated into national macroeconomic frameworks. Their contribution to development will depend on robust governance, consistency with fiscal and debt policies, and the ability to convert accumulated savings into credible productive investments. The capacity of African sovereign wealth funds to move from rent-management instruments to genuine long-term investment vehicles will depend on achieving this institutional balance.

IV. Debt and international capital markets

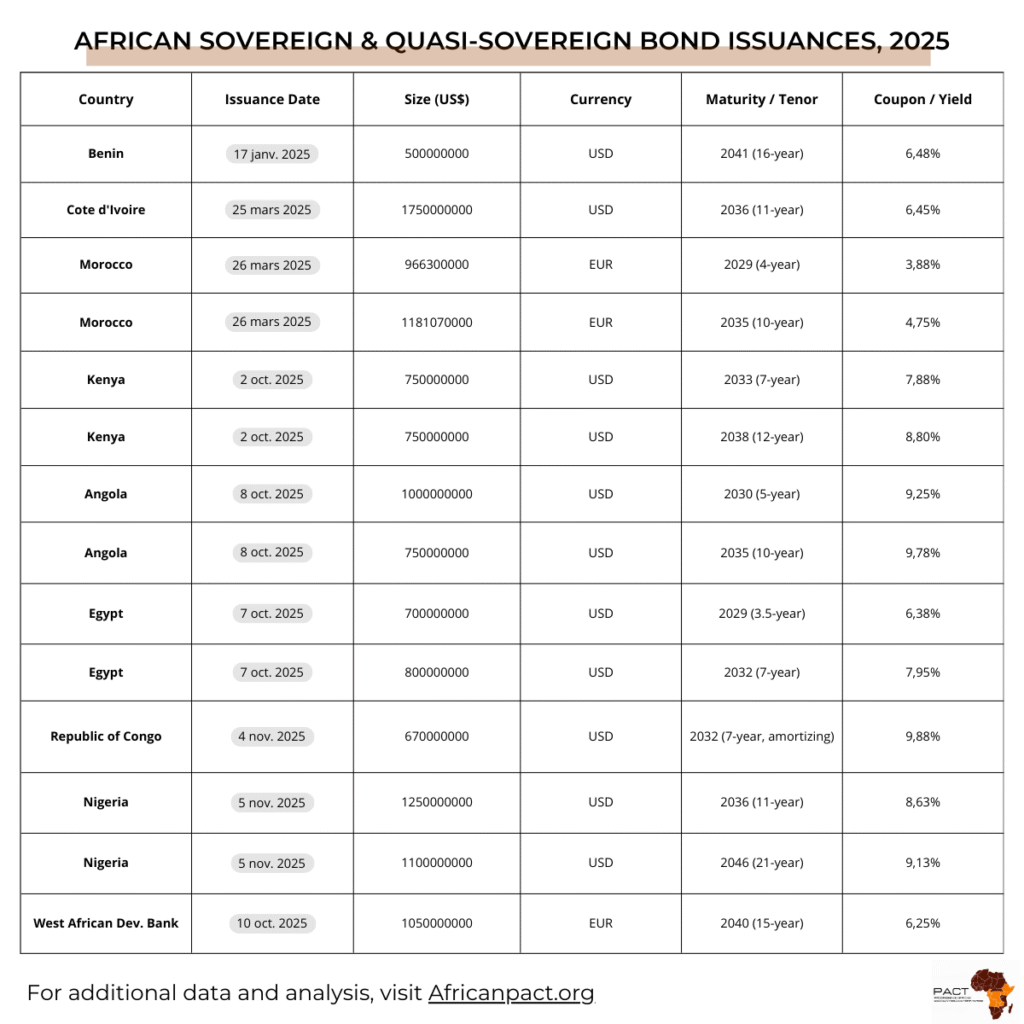

In 2025, access to international capital markets reopened for a limited number of African issuers after several years of closure. The analysis here focuses on foreign-currency issuances mobilizing international private capital, excluding domestic and regional issuances, which follow distinct dynamics. Within this perimeter, market access remained selective and costly, with transactions concentrated among a few sovereigns and with a growing differentiation of risk profiles.

Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria, Kenya, and Angola raised significant amounts in 2025, but at high cost, with coupon rates generally ranging from 6.5 percent to nearly 10 percent. By contrast, better-rated or quasi-sovereign issuers, such as the West African Development Bank and Morocco, benefited from more favorable conditions, underscoring the central role of institutional credibility, the macroeconomic framework, and perceived governance quality.

Debt functioned fully as a macro-financial signaling instrument. The capacity to issue influenced access to other forms of capital, shaped private-sector mobilization, and weighed directly on economic-policy decisions. In this context, the African Development Bank continued to play a targeted intermediation role through its own issuances, partial guarantees, and hybrid instruments aimed at improving risk perception, reducing the cost of capital, and extending maturities, without substituting for markets.

The return to markets, however, occurred mainly within a refinancing logic, focused on smoothing maturities and preserving market access rather than financing clearly identified structural transformations. This configuration heightens medium-term sustainability challenges, given the simultaneous rise in debt-service costs and refinancing needs.

In the coming years, the central issue will not be borrowing capacity alone, but the economic use of contracted debt. Debt is only a relevant instrument when it enhances leverage on private investment, durably lowers the cost of capital, and contributes to broadening the productive base, rather than supporting current expenditure or rolling over existing liabilities.

V. African Development Bank: strategic shift

In 2025, the African Development Bank underwent a governance transition as Dr. Sidi Ould Tah took office, against a backdrop of rapid demographic growth, substantial infrastructure needs, and heightened pressures on public debt. The new Presidency structured its roadmap around four pillars: capital mobilization, deepening African financial systems, translating demographic dynamism into productive capacity, and developing infrastructure that generates greater local value.

On the financial front, the seventeenth replenishment of the African Development Fund reached approximately USD 11 billion, a record level for the concessional window. Twenty-three African countries contributed around USD 183 million, strengthening the relative weight of regional resources.

The Bank’s current strategy places emphasis on transforming domestic savings into long-term productive finance. Pension and insurance assets, estimated at USD 700–800 billion, remain largely concentrated in short-term instruments or invested outside the continent. The institution is therefore acting on financial intermediation by deepening local-currency bond markets, strengthening prudential frameworks, and gradually integrating African financial centers. The African Domestic Bond Fund supports the construction of local yield curves and broadens the investor base for domestic debt.

To increase its lending capacity, the Bank has also made use of hybrid capital instruments, including an issuance of about USD 500 million in 2025 aimed at reinforcing lending headroom while preserving its AAA rating. Building on this approach, the Bank has stepped up the mobilization of international and private capital, including through formalized partnerships with financial centers such as London, in order to expand the access of African projects to global markets.

Finally, the creation of a pan-African financial coordination platform aims to reduce fragmentation in financing by aligning project preparation, funding flows, and implementation sequencing among governments, development banks, and private investors, particularly for large, capital-intensive regional infrastructure.

Taken together, these developments reflect an evolution in the Bank’s role within the African financial ecosystem. The institution is placing greater emphasis on structuring financing conditions by bringing together governments, institutional investors, the private sector, and SMEs. The chosen orientation favors a systemic approach that seeks better capital allocation, more coordinated execution of investment projects, and a more direct translation of financial flows into development outcomes.

VI. Domestic capital, pension funds, and SMEs: an incomplete mobilization

In 2025, the mobilization of domestic capital occurred mainly through regional markets, which have become a pillar of public financing. In unions such as WAEMU, treasuries increased local-currency issuances, combining short-term bills and medium-term bonds to cover budget needs and cash management. This dynamic, however, rests on a narrow investor base: commercial banks absorb the majority of securities, accounting for roughly 85 percent of demand.

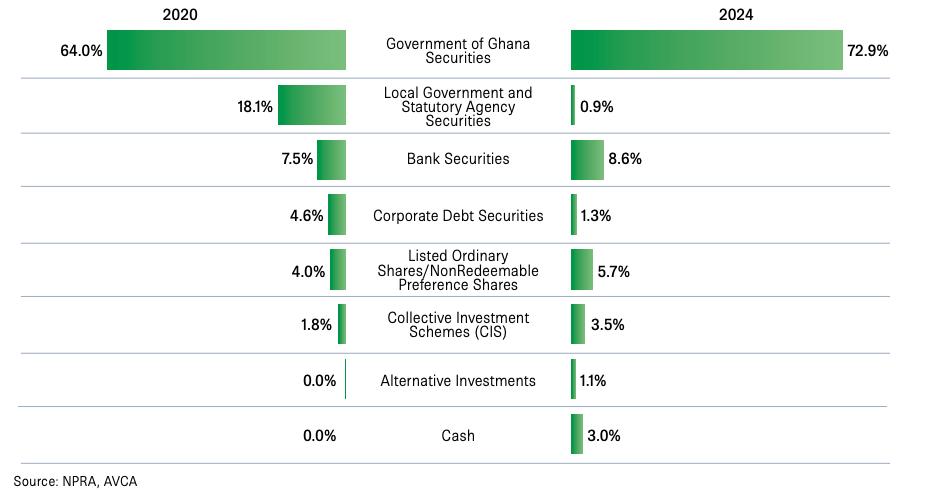

In this context, pension funds represent the principal reservoir of patient capital but remain only weakly engaged beyond sovereign debt. In several countries, their portfolios consist of 70–90 percent public securities and liquid assets, while exposure to SMEs, non-sovereign infrastructure, and long-term assets often remains below 5 percent. This configuration reflects less a shortage of savings than the effect of restrictive prudential frameworks, the absence of suitable intermediation vehicles, and limited risk-sharing mechanisms.

Ghana offers a telling illustration of this paradox. Despite the growth of pension-fund assets and a clear policy ambition to redirect savings toward domestic investment, portfolios remain largely concentrated in public debt. The ongoing debates have shown that the main constraint is not the availability of capital, but the capacity to structure instruments that comply with prudential requirements and can channel institutional savings toward SMEs and productive long-term investment.

This financing architecture has a direct impact on SMEs. Although they constitute the core of economic activity and employment, they remain structurally excluded from the main domestic financing channels. Liquidity mobilized by governments through regional markets and held on bank balance sheets circulates only weakly toward the productive economy. The priority is to enhance the channelling of domestic capital toward productive uses by more fully integrating long-term investors and establishing effective linkages between regional markets, institutional savings, and SME financing.

VII. Fintech in West Africa: SME Integration

In 2025, fintech remained one of the most dynamic segments of the private sector ecosystem in West Africa, while entering a more clearly defined phase of institutional structuring. The BCEAO continued to strengthen the regulatory framework applicable to payment institutions and fintech actors, with the objectives of financial stability, consumer protection, and clearer requirements in terms of licensing, governance, and supervision. This evolution confirms fintech as an integrated component of the regional financial architecture.

Within this framework, several players began an institutional upgrading process. Wave is the most visible example: after profoundly reshaping payment and mobile-money usage, particularly in Senegal, the company obtained a banking license. This change expands its scope of activity and strengthens its role in formalizing the cash flows of micro-entrepreneurs and informal SMEs. However, it does not resolve the central constraint faced by these enterprises, which remains access to medium- and long-term credit.

At the same time, investor appetite for some fintechs oriented toward business services has remained tangible. Moniepoint’s USD 200-million capital raise illustrates the continued interest in models that directly target SMEs and informal actors, built around payments, cash-flow management, and the collection of transactional data.

One conclusion stands out from these developments: fintech does not replace banks or capital markets. Rather, it constitutes an entry point into the financial system for a large share of informal SMEs by making transactions traceable and generating usable data. Its main contribution at this stage lies less in the volume of credit extended than in the gradual formalization of cash flows and the creation of transactional histories that can reduce information asymmetries between SMEs and lenders.

The challenge therefore goes beyond financial inclusion to its productive translation. The ability of fintech platforms to connect with banks, institutional investors, and risk-sharing mechanisms will determine whether current progress translates into durable access to finance and an upgrading of informal SMEs.

Human Development First

The financial dynamics examined in this editorial converge on a simple but decisive truth: capital has economic and political meaning only when it translates into measurable improvements in people’s lives and productive capacity. In 2025, this truth took on renewed urgency in a context marked by demographic pressure, social vulnerability, climate risk, and persistent insecurity.

This is a concrete and urgent question: how can current needs be met without narrowing the horizons of future generations?

Most African economies face a structural constraint. Rapid population growth increases demand for education, health, and energy at the very moment when fiscal space to meet these needs is tightening. When these foundational investments advance too slowly, productivity stagnates, formal employment develops insufficiently, and demographic change loses its promise of becoming a demographic dividend. Behind the statistics are children leaving school early, families without reliable electricity, and young graduates unable to find their first job.

These imbalances have direct macroeconomic and security consequences. A large cohort of young people who are poorly educated and weakly integrated into productive sectors is pushed toward economies of survival, where illicit activities, criminal networks, or armed groups can appear as alternative pathways to income and belonging. In several fragile contexts, the persistence of violence is explained as much by economic incentives as by ideology.

The protracted crises in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan, and South Sudan illustrate this nexus. Although their triggers are political or geopolitical, their endurance is rooted in long-standing deficits in human capital, access to energy, and the creation of productive jobs. Humanitarian action alleviates immediate suffering, but it cannot, on its own, transform the underlying economic conditions that make these crises recurrent.

Seen from this perspective, debates on capital markets, sovereign wealth funds, debt, fintech, and domestic capital regain their coherence. These are not ends in themselves, but instruments. Their relevance is measured by their capacity to finance human capital accumulation, absorb demographic momentum, create sustainable employment pathways, support development, and build shared prosperity on the African continent.

The real test for African strategies will not be the ability to raise funds, but the alignment of financing with productivity and human development. The task ahead is clear: convert capital into capabilities, liquidity into livelihoods, and growth into broadly shared dignity. Credibility will depend on whether investments improve public services, expand reliable and affordable energy, and create decent jobs. Africa’s development paths will be shaped where the real economy connects with social cohesion and effective risk management.

Sources and references

- African Business. (2025). AfDB president Sidi Ould Tah on his first 100 days. https://african.business/2025/12/finance-services/afdb-president-sidi-ould-tah-on-his-first-100-days

- African Pact. (2025a). Building futures: Education in a rapidly growing Africa. https://africanpact.org/2025/01/30/building-futures-education-in-a-rapidly-growing-africa/

- African Pact. (2025b). Mali’s lithium revolution: A catalyst for regional development and integration. https://africanpact.org/2025/01/21/malis-lithium-revolution-a-catalyst-for-regional-development-and-integration/

- African Pact. (2025c). Public lenders and capital markets in Africa. https://africanpact.org/2025/08/28/public-lenders-capital-markets-africa/

- African Pact. (2025d). Côte d’Ivoire: A $433m sustainability-linked loan. https://africanpact.org/2025/09/08/cote-divoire-sustainability-linked-loan-433m/

- African Pact. (2025e). Botswana diamonds and economic diversification. https://africanpact.org/2025/09/23/botswana-diamonds-diversification/

- African Pact. (2025f). Africa’s critical minerals: From resources to industrial power. https://africanpact.org/2025/10/02/africas-critical-minerals-from-resources-to-industrial-power/

- African Pact. (2025g). BOAD eurobond: West Africa’s financial maturity. https://africanpact.org/2025/10/15/boad-eurobond-west-africa-financial-maturity/

- African Pact. (2025h). Africa’s energy frontier: Electrification, investment and the power gap. https://africanpact.org/2025/10/22/africa-energy-frontier-electrification-investment-power-gap/

- African Pact. (2025i). Moniepoint raises $200 million as African fintech matures. https://africanpact.org/2025/10/26/moniepoint-200-million-raise-african-fintech/

- African Pact. (2025j). Nigeria’s return to the eurobond market in 2025. https://africanpact.org/2025/11/14/nigeria-2025-eurobond-return/

- African Pact. (2025k). Designing Africa’s financial future: The AfDB’s bid to build markets that match its demography. https://africanpact.org/2025/11/25/designing-africas-financial-future-the-afdbs-bid-to-build-markets-that-match-its-demography/

- African Pact. (2025l). Ivory Coast’s Ambition 2035. https://africanpact.org/2025/12/03/ivory-coast-2035-ambition/

- African Pact. (2025m). Simandou: Guinea’s megaproject and its macroeconomic implications. https://africanpact.org/2025/11/19/simandou-guinea-megaproject/

- Institut de relations internationales et stratégiques (IRIS). (2025). Fin de l’USAID : conséquences internationales et multisectorielles. https://www.iris-france.org/fin-de-lusaid-consequences-internationales-et-multisectorielles/

- Reuters. (2025, December 29). U.S. pledges $2 billion in humanitarian support, State Department says. https://www.reuters.com/world/us/us-pledges-2-billion-humanitarian-support-un-state-department-says-2025-12-29/